Burden of proof. The construction of Visual Evidence from the Holy Shroud to Satellite Images

27 January – 1 May 2016

Exhibition conceived by Diane Dufour.

With Luce Lebart, Christian Delage and Eyal Weizman.

With the contribution of Jennifer L. Mnookin, Anthony Petiteau, Tomasz Kizny, Thomas Keenan and Eric Stover. A coproduction by Le Bal (Paris), Photographers’ Gallery (London) and Netherlands FotoMuseum (Rotterdam).

Set-up conceived by Marco Palmieri.

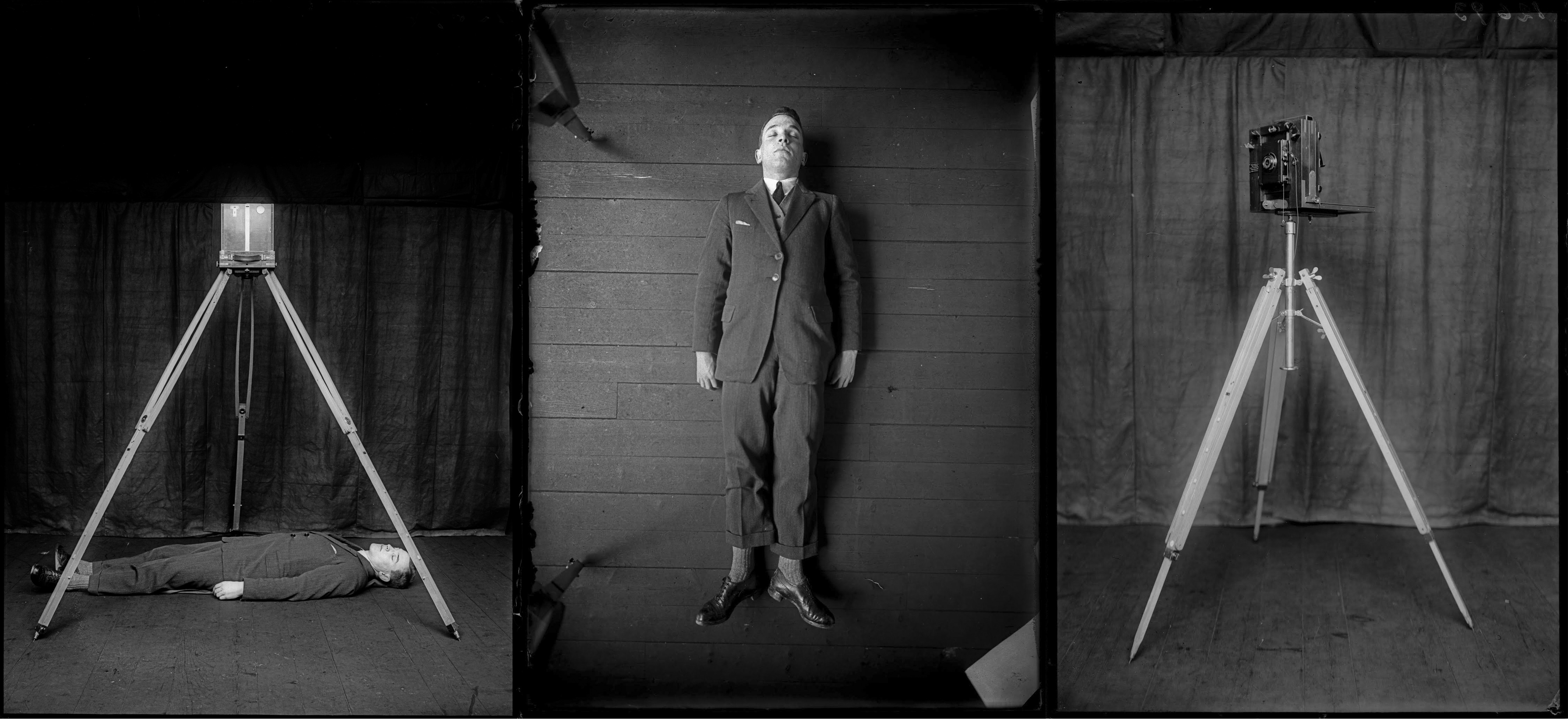

The exposition analyses the history of forensic photography and displays a collection of pieces spanning over one hundred years of history: from the first photos appearing in courts of law to the satellite photos used by human rights organisations to report the killing of civilians, like after drone attacks. These powerful photographs are very different from one another but share the terrible violence that they document and substantiate.

CAMERA has selected eleven case studies in order to illustrate a scientific approach to photography as a tool in the hands of justice. Compared to the research conducted in the fine arts field, this one is certainly very different but it does not lack a sort of grim charm, dignified by the weight of history.

Are artistic and forensic photography really that different, though? The former has often questioned the actual verisimilitude between photography and reality, while the latter has made truth seeking and documentation its raison d’être.

This exhibition explores both the power and the limits of photography in the quest for the truth. The image shows its power, more shocking and more convincing than words or figures could ever be. The limit is in the technique: it often disproves the idea that the photographer’s lens is an unerring eye – observing and registering all – that can capture the moment and stop the time.

It becomes clear that the truth is not just reconstructed but is actually built in that moment to be later defended by proofs – among which the images play the main role. Therefore, it is not enough to exhume mass graves of Kurd victims of the genocide committed by the Iraqi army in 1988. In 1992 a photographer from Magnum agency worked with the activists in the search for evidence, and meticulously documented the disinterment in order to prove the existence of those victims so that they could receive justice. Putting the Nazi hierarchs on trial is not enough: the horror of extermination camps was photographed by the Allies following precise rules and the video that followed them was the most important count charged on the accused in Nuremberg. The truth coming out from this evidence is everything but plain: it has been hard to obtain and no image will ever be seen enough times by enough people so that it becomes immortal and safe from historical revisionisms.

In Italian, ‘camera lenses’ have been called “objectives” in hopes that photography would protect us from the imprecision and the doubts of subjectivity. Nevertheless, a photo can have more than one interpretation, and, to this day, dire geopolitical and humanitarian consequences could follow. Are there, or are there not, traces of the ancient Bedouin cemetery of Koreme in the Negev in the aerial photographs taken but the RAF at the end of World War II – before the birth of Israel? The people saying that you cannot see a Bedouin cemetery in the noised and foggy pictures taken 70 years ago are not only arguing about some details in old photos. They are equally stating that the thousands of Palestinian families who still live in the area are squatters that have to be sent away from their homes, and this is an additional proof of the terrible power that pictures can have.

An intense and multi-layered exhibition, that talks about our dark side and our desperate need for certainties.

The exhibit comes with a catalogue: Images à Charge. La construction de la preuve par l’image, co-produced by LE BAL and Xavier Barral Éditions, available in English and French. Curated by Diane Dufour, with contributions by Christian Delage, Thomas Keenan, Tomasz Kizny, Luce Lebart, Jennifer Mnookin, Anthony Petiteau, Eric Stover, and Eyal Weizman. The book is 240 pages long, with 280 pictures.